Celebrating Black History Month.

In honor of Black History Month in the Netherlands, the month of October, SCDAI has chosen 4 out of the countless important figures and events in Black history of the Netherlands that should be included in the history books. This series aims to exemplify how holistic #BLACKHISTORYEDUCATION, that goes beyond the enslavement of people during the transatlantic slave-trade and segregation, represents Black people in a multi-dimensional way. Shining a light on the resilience, talent, success and courage of Black people as well.

Particularly here in the Netherlands, it helps us better understand the political, societal, academic, cultural and economic relationship of the Netherlands with the predominantly Black (former) colonial territories. Furthermore, this series was researched and written out by Black women, prioritizing sources by Black authors, researchers and platforms. Setting the example for how we can and we must diversify our curricula to achieve holistic education.

#1 - Dr. Sophie Redmond

We're starting off strong with Dr. Sophie Redmond, who was the first black female doctor in Suriname and an advocate for Surinamese culture and language.

Who was Dr. Redmond?

In 1925 she started her education at the Medical School and she graduated in 1935. She was the first black woman to graduate from this school. Sophie's father objected to her desire to become a doctor, and wanted her to be teacher like him. And at first, the management of the medical school refused to enroll her. However this wasn't because she was a woman, but rather because of the color of her skin.

Earlier, Selly Fernandez, a Jewish woman, had completed her medical degree. Edna Gravenberch, who graduated a year before Redmond, came from the same ethnic group as Redmond, but was so light-skinned that she was not considered a "negro". Sophie Redmond, on the other hand, had very dark skin and therefore encountered more resistance. In 1935 she passed her exams as the first black woman and established herself as a self-employed doctor. She was called 'datra fu potisma' (doctor of the poor) because she often gave free consultations to people who had to live on little.

What did she do?

Dr. Redmond was an activist as well, who committed herself to the Surinamese population. She provided a lot of information about health, hygiene and social issues through the weekly radio program 'Datra, mi wan' aksi wan sani' (Doctor, I want to ask something). She was a board member of various organizations, such as a children's home, a charitable association, and the theater company 'Thalia'. For 'Thalia' she wrote several plays with an informative element, such as about the elections or blood transfusion. She not only wrote, but also played along.

Sophie Redmond loved the Surinamese language and culture, she liked to wear the Creole costume, the koto, and also organized kotomisi shows. She preferred to speak in Sranantongo and stimulated research into Surinamese medicinal herbs. Redmond died young, at the age of 48, while still full of plans. The street in Paramaribo where she last lived is now called the Doctor Sophie Redmonstraat. A school is named after her and a sculpture of her is in the Academic Hospital in Paramaribo.

Why should she be in the history books?

The Intersectionality of Black Women.

While being a doctor was difficult for women and black people in general at the time, we must acknowledge how it was a greater struggle for Dr. Redmond because she was both. By learning her story we are better able to understand that because of their intersectionality, black women have experienced a particular kind of exclusion that continues to denude them of opportunities and holistic representation. Having this knowledge, teaches us to aim for equitable practices.

A Pioneer in preserving culture that survived colonialism.

Western settlement and colonialism has wiped out or endangered so many cultures and languages. And we are often victims of western-normativity when we allow the replacement of our culture, often by deeming it "uncivil", "unproductive" to capitalism or as something to be ashamed of. It is enlightening and inspiring to learn about someone who so strongly advocated for its preservation.

A role model. Specially for women in STEM & Politics.

Dr. Redmond is a role model of perseverance and hard work for anyone. But for women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM), where even in Europe only 41% are women (and in the US only 26.7%), she is an imperative role model.

Did you know? In 1950 Sophie Redmond caused a stir by running as an independent candidate in the elections. Because of the electoral system in force at the time and the fact that as an independent woman in politics she posed a threat to the male political figures, she was not elected.

A story of hope and success.

Black History Education is filled with pain, sorrow and mistreatment. While it is important to learn about how slavery and segregation have impacted our society, black children deserve to see themselves represented in stories as resilient, successful and beloved people - like Dr. Sophie Redmond.

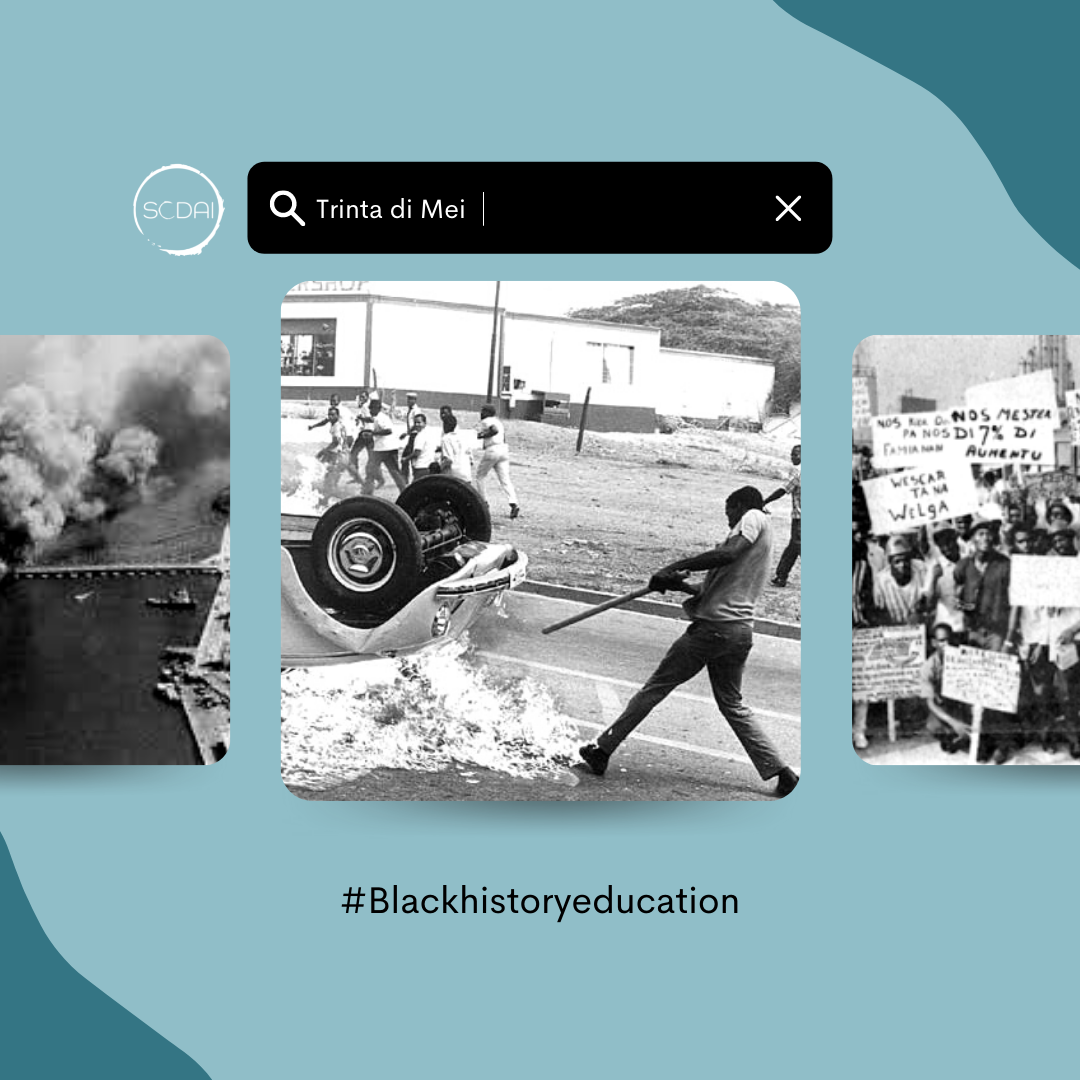

#2 - "Trinta di Mei"

"Trinta di Mei", which translates to "Thirtieth of May" is an important date in the islands that formed the (former) Netherlands Antilles. The uprising was the foundation for the political and economic emancipation of the islands. An emancipation that is still being fought for in 2021.

What was "Trinta di Mei"?

The 1969 Curaçao uprising was a series of riots lasting from May 30 (translated to "Trinta di Mei" in Papiamento) to June 1, 1969. They arose from a strike by Shell workers led by the unions. It was a turning point in relations on the island and in the awareness and emancipation of Antilleans.

What caused the uprising? In 1918 Shell opened a refinery in Curaçao and it continually expanded until 1930. The plant production peaked in 1952, which caused an economic boom and employment, particularly for immigrants from Suriname, Madeira and the Netherlands. By 1969 employment decreased significantly and Shell only employed around 4000 people. Unemployment reached 8000 in 1966 and workers of color and workers with little to no academic education were particularly affected.

Why were people angry?

1. The oil industry brought a number of civil servants (mostly) from the Netherlands. This caused a segregation in Curaçao into 'landskinderen' (those in Curaçao for generations) and 'makambas' (new European inhabitants).

2. Another point that emerged was the relationship of the Netherlands Antilles, and Curaçao in particular, with the Netherlands. According to the Charter form 1954 onwards, the Netherlands Antilles, like Suriname until 1975, were part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, but not of the Netherlands itself. Foreign policy and national defense were Kingdom affairs. Other issues were settled at the island level. Although this system had its proponents who pointed out that managing their own foreign relations and national defense would be too expensive for a small country like the Netherlands Antilles, many Antilleans saw it as a continuation of the area's subaltern colonial status.

3. Mass media was also one of the causes of the uprising. The people of Curaçao were well aware of the events in the United States, Europe and Latin America. In addition to their access to media, many Antilleans traveled abroad, including many who have studied abroad. The situation of Black Curaçaoans was comparable to Black people in the United States and Caribbean countries such as Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados. The movement that led to the 1969 uprising used many of the same symbols and rhetoric as Black Power and civil rights movements in those countries.

4. The center-left Democratic Party (DP) had been in power in Curaçao since 1954. The DP was mainly associated with the white segments of the working class and Black people criticized it for promoting mainly white interests and the DP's inability to live up to expectations that it would improve workers' working conditions. The sixties also saw the rise of radicalism in Curaçao. Many students went to the Netherlands to study and some returned with radical left ideas and founded the Union Reformista Antillano (URA) in 1965. The URA established itself as a socialist alternative to the established parties.

How did it happen?

Curaçao was seen as an unlikely place for political unrest, despite low wages, high unemployment and economic disparities between Black people and white people. After two minor strikes in the 1920s and another in 1936, a Shell workers contract committee was set up. In 1942, workers with Dutch nationality were given the right to elect representatives to this committee. The Curaçao Federation of Workers (CFW), represented construction workers employed by the Werkspoor Caribbean Company, a subcontractor of Shell. The CWF would play an important role in the events leading up to the uprising. Among the unions that criticized the AVVC was the General Dock Workers Union (AHU), which was led by Papa Godett and Amador Nita and was guided by a revolutionary ideology that sought to overthrow the remnants of Dutch colonialism, especially discrimination against Black Curaçaoans. The labor movement before the 1969 uprising was very fragmented and personal hostility between union leaders exacerbated this situation.

In May 1969 there was a labor dispute between CFW and Werkspoor. Central issues were Antillean Werkspoor employees received lower wages than workers from the Netherlands or other Caribbean islands as the latter were compensated for working away from home. Secondly, Werkspoor employees performed the same work as Shell employees but received lower wages. About 400 Werkspoor employees went on strike on 6th of May. On May 8, this strike ended with an agreement to negotiate a new contract through government mediation.

These negotiations failed, leading to a second strike that began on May 27. The dispute became increasingly political as union leaders felt the government should intervene on their behalf. As the conflict progressed, radical leaders, including Amador Nita and Papa Godett, gained influence. On May 29, as a moderate workers' party was about to announce a compromise and postpone a strike, Nita took that man's notes and read out a statement of her own. He demanded the resignation of the government and threatened a general strike.

May 30th 1969

On May 30, more unions announced strikes in support of the CFW’s struggle against Werkspoor. Papa Godett called for a march to Willemstad 5000 workers took part (mainly Black) to protest. The march became more violent with fires and looting of companies with particularly bad reputation in treatment of their employees and poor working conditions. In the end Willemstad was severely impacted by the fires but a compromise was reached with Werkspoor. Shell workers would receive the same wages whether they were employed by contractors or not and independently.

The focus of the uprising shifted from economic demands to political goals. Union leaders, both radical and moderate, demanded that the government resign and threatened a general strike. They argued that failed economic and social policies had led to the grievances that led to the uprising. On May 31, The Aruban delegates agreed to the demand for the resignation of the government and announced that Aruban workers would also go on a general strike if it was ignored. In the end the uprising achieved its economic demands and political demands. On June 3 new elections for September was announced in fear of further strikes and violence.

After "Trinta di Mei"

1. It initiated a number of political, social and cultural changes in Curaçao. Firstly, the then completely white government of Curaçao resigns. "Awor nos ta manda" (now we take the reins) is the new slogan. Stanley Brownalong with Godett and Nita founded the party Frente Obrero i Liberashon 30 di May (FOL), with which they won three seats in the states after the first elections.

2. Author Cola Debrot, then governor, resigns and is replaced by Ben Leito: Curaçao's first Black governor. The revolution also started the appreciation of the Black Curaçaoan for his own culture. Old traditions are rediscovered and new cultural expressions flourish. For example, there is a commemoration for the first time of the slave revolt that Tula led in 1795.

3. This also resulted in the first Curaçao Academy of Visual Arts, where a new vision of art flourishes. They distance themselves from Western conventions and the Curaçao citizen discover how art can help to investigate and promote one's own identity.

4. In any case, the uprising has had a lot of positive effects on a cultural level: since 1969, dark skin color is no longer a sign of inferiority and oppression, but of strength and beauty. Or as Brown says: 'From that day on, we Curaçaoans learned to look at ourselves with different eyes.'

Unsung Heroes

Most of the attention remained on male union leaders in the uprising of May 30th while the role of women was underexposed. One of the women was Emmy Henriquez. She was involved in the Vitó magazine and was imprisoned for 10 days and lost her job. She was very important in formulating the thoughts and communication of the struggle for social justice.

Before the revolution of May 30, 1969, the women of Curaçao were already activists. Moreover, the revolution in Curaçao is not separate from the emancipation process that took place in the Caribbean.

Women have always played a major role in emancipation. The 1969 movement saw women applying for positions on union boards. After May 30th there was a much greater awareness. Women became more aware of the changes that needed to take place.

The injustice against women, especially women who worked in shops on May 30, 1969, was important in the approach to social justice. Yet most of the attention goes to the male union leaders. By focusing too much on the moment of May 30 and the battle, the place, the voice, and the importance of women has been lost.

#3 - Philomena Essed

Philomena Essed is a professor of Critical Race, Gender, and Leadership at Antioch University in the United States and an affiliated researcher for Utrecht University’s Graduate Gender program.

Who is Philomena Essed?

Philomena Essed was born in 1955 in Utrecht and is the daughter of Surinamese parents. Her father, Max Essed, was a pediatrician. Her mother, Ine Corsten, had a social and leading role in the Roman Catholic community in addition to raising a large family. Essed spent her childhood alternately in Suriname and the Netherlands. From the age of fourteen, she lived in Nijmegen, and in 1974 she moved to Amsterdam. In 1983 Essed obtained her master's degree in cultural anthropology from the University of Amsterdam, where she obtained her doctorate cum laude in 1990 as a doctor of social sciences.

What has she done?

Essed is a pioneer in the field of racism research and the simultaneous operation of different dominance systems. In the Netherlands, she is best known for her books Everyday Racism (1984), Insight into everyday racism (1991), and Understanding Everyday Racism (1991). Her work is internationally renowned for its originality and for introducing groundbreaking concepts such as ‘everyday racism’, 'gendered racism', and 'entitlement racism', as well as the phenomenon of 'social and cultural cloning' in a handful of articles.

In Everyday Racism, Essed uses interviews with Surinamese and African-American women to paint a picture of the prejudices and racism they experience on a daily basis. Through the lens of the groundbreaking Everyday Racism, we see the implicit workings of discrimination and prejudice and the way deep-rooted racism is expressed.

The book Everyday Racism is still relevant and was reissued in 2018. To this new edition, Philomena Essed added a new chapter on 'entitlement racism', the racism justified by an appeal to freedom of expression. In addition to her academic work, she has been an advisor to governmental and non-governmental organizations, nationally and internationally. She is a deputy member of the Netherlands Institute for Human Rights and in 2011 the Queen of the Netherlands honored her with a Knighthood.

#4 - Tula

"We have been abused too much, we do not seek to harm anyone, we are just seeking our freedom. French Negroes gained their freedom, Holland was occupied by the French, then we must be free here"

Who was Tula?

Tula, also known as ‘Rigaud’ named after the Haitian General Benoit Joseph Rigaud (one of the heroes of the Haitian revolution) was the leader of the great slave revolt of 1795 in Curaçao. Tula was enslaved to the Knip plantation, owned by Casper Lodewijk van Uijtrecht. Little is known or preserved in documents of his personal life. Reverend Bosch, who arrived in Curaçao in 1816, wrote that he had spoken to people who had known Tula alive. They remembered him as a man of strong stature and eloquence. He worked with other leaders, such as Bastiaan Carpata and Louis Mercier, to end slavery. He argued for the freedom of all enslaved people in Curaçao, Tula used arguments from politics, from the changing regulations of the time and from Christian doctrine.

He gathered fellow enslaved people and took the initiative to lay down work on the 17th of August 1795, together with about forty to fifty enslaved people, to go to his owner Casper Lodewijk Van Uytrecht to plead for their freedom. This was the beginning of the largest slave revolt in the history of the Netherlands Antilles. Under Tula's leadership, about two thousand slaves went to the governor in Willemstad.

Curaçao, August 1795

On August 17, 1795, Tula and fellow enslaved people went to the owner of Knip, Casper Lodewijk van Uytrecht, and told him that they were claiming their freedom. There, enslaved people from other plantations in the area also joined them. The next day, Tula makes his headquarters at Porto Marie plantation. The insurgents captured weapons and ammunition at the Knip and Santa Cruz forts. On August 19, they won the first confrontation with the colonial army.

A negotiator is then sent to Tula; Father Jacobus Schinck. Tula tells him, as you can read above, that the enslaved want nothing but their freedom. The father tries to convince him that the well-armed and trained colonial army is stronger than the group of enslaved people. Thus in response, Tula appeals to the Christian morality of the cleric. However, it is not successful.

On August 20, and then again from August 25 to 30, brutal fighting took place between the army and as many as two thousand enslaved people. In which many people died, many were injured, and many fled.

The insurgents are encouraged to surrender. High rewards are offered for those who capture the leaders of the uprising. Captured insurgents are forced to confess on the rack, while some are hanged. In the weeks following the battle, the leaders are arrested one by one. They are all publicly tortured and executed in Willemstad. The "slave revolt" ended brutally and Tula managed to hide in the wilderness for some time but was eventually captured by a fellow enslaved person after a hefty bounty was placed on his head and he was handed over to his owner.

Why should this revolt be in the history books?

A large proportion of the enslaved people on the west of Curaçao

were involved in the uprising, with as many as fifteen percent of all enslaved people on the entire island fighting on August 25. After Tula's death, the Dutch authorities made sure that plantation owners would start treating enslaved people "better" to prevent more riots. On November 20, 1795, new rules of the infamous "Slave Regulations" for the treatment of slaves were published and strictly enforced. For example, Sunday became a day off again, regulations were introduced for a maximum working time and a minimum distribution of food and clothing. All in all, the uprising of 1795 marks the beginning of the freedom struggle of enslaved people on Curaçao. Tula was the starting point of freedom for Black people in Curaçao until slavery was officially abolished on July 1, 1863.

By omitting stories of people like Tula from the history books, we reinforce false narratives about the abolition of slavery. We indoctrinate people with the belief that slavery ended because enslavers and colonialist had a "change of heart". Disregarding the courage and sacrifices enslaved people made that continuously led to less than the bare minimum - like how it happened to Tula and the people of Curaçao.

Sylvana Simons, politician of Bij1, stated while Tula’s legacy lives and is remembered in Curaçao few people in the Netherlands know about this legacy. The struggle for freedom and humanity has been a part of the Black history of the Netherlands for centuries and has been excluded from education. When we actively exclude Black history and stories of Black leadership we continue to replicate racism and colonialism in Dutch society.

Watch the full speech (DUTCH) by Sylvana Simons about the Netherland's past and current relationship with the Dutch Caribbean.

Sources https://atria.nl/nieuws-publicaties/bijzondere-vrouwen/vrouwelijke-pioniers/sophie-redmond/Dr Sophie Redmondhttps://archive.org/details/socialmovementsv0000ande/page/n3/mode/2up "The Complexity of National Identity Construction in Curaçao, Dutch Caribbean" https://www.stedelijk.nl/nl/digdeeper/30-mei-1969-willemstad http://curacaochronicle.com/social/remembering-the-uprising-in-curacao-may-30-1969/Geen erkenning voor vrouwen tijdens en na opstand 30 mei 1969Philomena EssedPhilomena Essed, PhDhttps://www.theblackarchives.nl/de-philomena-essed-collectie.html https://www.trouw.nl/nieuws/philomena-essed-mijn-drijfveren-zijn-niet-persoonlijk~b7a02ddc/?referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.nl%2F https://www.nationaalarchief.cw/geschiedenis/tula https://www.curacaohistory.com/Slavenleider Tula († 1795) – Nationale held van Curaçaohttps://www.slavernijenjij.nl/het-verzet/opstand-op-knip/